In the kitchen of her lovely old redbrick house, Nell McCafferty apologises for the lack of biscuits. As I sit down at the table and she makes tea, I get the feeling that this is the kind of kitchen where visitors are regularly treated to home baking. The house, the kitchen, the invitation to tea send me certain messages. Homemaker. Breadbaker. It is an interesting backdrop for a woman who is known as a cantankerous feminist, barricade stormer and some-time IRA defender.

Feminism and republicanism are very much in the news at the moment. After the murder of their brother, Robert McCartney, by IRA members, The McCartney sisters have dominated news about Ireland. Their demands that the killers be brought to justice have thrown traditional support for the IRA in Catholic communities in the North into question. McCafferty, who describes in her book how she was shunned in the past because of her “refusal to condemn a neighbour’s child”, has her roots in that same community. What does she make of the events? “I think it has changed everything. It is obscene what happened to those men [a number of men were beaten in the attack]. The McCartney sisters are from a Republican background, and would have supported the IRA as defenders of the community. Now that has changed – what they see, what we are all seeing is that the IRA will kill you, kill their own. It is a terrible shock that members of the IRA could conduct themselves like a murderous gang”.

But was it not well known already, what the IRA was up to? Can it really be a surprise that an army kills? McCafferty vehemently rejects this. “This is different. I am not saying I am suddenly waking up and smelling the coffee. Sure, human rights were violated, we were under siege and there was a war on – but not like this. And now the war is over, has been over for 9 years. Sinn Féin wanted the IRA to stand down. OK, there were a few difficulties with certain people, but we thought the IRA wanted the IRA to stand down. Now I don’t know. Perhaps there will be a split, which would be terrible because it could bring back the guns”.

She is critical of media who she feels have not covered the story well enough – not spelling out exactly what happened on that night in Maginnis’s pub in Belfast. She believes people need to know what happened to understand why this is a real watershed. “The community is deliberately out on the streets applauding these women. This is the hand of the community in the back of the IRA saying, ‘Go now’. Once women sanction revolution, there’s no stopping it”.

Women and rebellion is something McCafferty knows a lot about. Having grown up in Derry, she was at the centre of Northern Ireland’s civil rights movement for equal votes, homes and jobs for Catholics. McCafferty was there on Bloody Sunday in 1972, when British soldiers shot dead 14 marchers in Derry. She also campaigned on behalf of republican women in jail. She moved to Dublin in 1970, and as a journalist opened many people’s eyes to what was happening to the most vulnerable in Irish society when she wrote about the children’s courts. She soon became part of a small but vociferous group of women who started the campaign for equality and women’s rights. She went on the famous contraceptive train – a group of Irish women went to Belfast, stocked up with condoms, pills (which, she reveals in her book, were actually aspirin, but customs never knew that) and other illegal articles and brought them back to Dublin. Here they were met by police and waiting media. Yes, it is true: 30 years ago, contraceptives were still illegal in the Republic. Pints were another thing women could not have – and so the same women went in to a famous pub in Dublin’s city centre, ordered 40 brandies, waited for them to served, then ordered a pint. The barman refused, and they in turn never paid for the brandies.

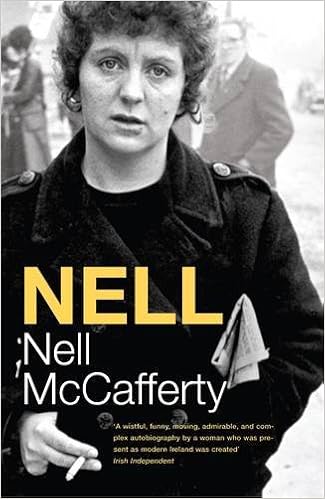

Nell McCafferty’s autobiography, Nell, published in November 2004, is full of great stories both from the civil rights, and women’s struggles. Despite dealing with deadly serious issues, McCafferty says feminism was fun. Her wit, compassion and sense of the ridiculous, used with such great effect in her journalism and campaigning, are much in evidence throughout the book.“We enjoyed the struggle, at least at the beginning. It was like shooting fish in a barrel, the obstacles to women were incredible, ludicrous, and stood out like a sore thumb. Ireland was full of men in suits who never had to deal with the likes of us before, and to see them challenged by someone as formidable as Mary Robinson – it was great. It is terrific if you are a revolutionary and you can achieve the revolution in a short time!“

Although not now actively involved with any organisation, McCafferty is still considered a prominent feminist, and regularly asked to “do gigs”. They day we met, she was due to speak later that evening on the subject “Has feminism gone too far”. She says the organisers have assumed she would be on the politically correct side, but “perhaps they should not be so sure”. She says she wonders if life has really become better for women as they deal with all the new pressures of juggling work and home, marriage breakdown, and running several families. “At first it was so simple, the obstacles so obvious. Now you are dealing with all the complicated stuff – three jobs, childcare, commuting, three children by three fathers. I do not have the answer, and I am glad I don’t have to deal with it. My excuse is always: don’t ask the prophet for a blueprint! I prophecised that we must work outside the home, but I never said how it would be done exactly. I just sketched the big picture, someone else deal with the details. I have forgiven myself for not providing the blueprint: that is not my job – someone has to look at the big picture first! I keep asking, and I really want to know, how are you going to make it work? Who is out there looking for a solution? I am bemused there is no great cry from women, and men; but I guess it is just a fallow period at the moment. Change will come. I think it takes 20 – 30 years for each generational change to really seep through. And jobs for women outside the home have only really happened in Ireland in the last ten years. But I do wonder, are you all happier now!? “

It is interesting that the role model for this feminist prophet was a traditional homemaker – her mother Lily. Central to McCafferty’s book is a fascinating and moving portrait of her mother, a truly remarkable woman who seems also to embody McCafferty’s statement about women sanctioning the revolution – as well as feeding the revolutionaries! Lily jumps off the pages and we see clearly how she inspired and supported Nell throughout her life. “My mother was one of the last of the full-time homemakers. We lived like royalty, she did everything for us. She never had her own job, and I know she would have liked to have her own money and not have to wait for my dad to hand it over. But she loved looking after us, and lots of other people too: she always had an open house where everyone was welcome. In 1968, when we were all reared, in a way she was redundant – but then civil rights happened, she became active in local politics and her house became a political salon and part-time refuge. Our house was always at the heart of the local community, and my mother was very much at the centre of it. All the neighbours came to my mother with their problems. There were a lot of things people could not talk about –but mammy would talk about it for them!”

However the one thing that could not be discussed was the fact that Nell was gay. Despite their terrific relationship, it remained a closed subject. Yet McCafferty opens her book with a declaration of her sexuality. She says she was “terrified” of her mother’s reaction. “Once the book was out there could be no ambiguity anymore.At the start, I was not sure if I could publish it while she was still alive. When I started the book, I decided to write everything down, and said to myself I could always take things out! But when it was done, – well, I felt this was the time, I had to be honest. So I took a deep breath and sent it off. I was terrified though, of how my mother and the neighbours, our street, would react. They have been through everything else – war, wife beating, rape, marriage breakdown –this was the last taboo."

Lily McCafferty died just before Christmas, soon after the book was published. McCafferty is very glad now that her mother got to see it. “Thank God I got the book out. It would have been a big ache in me if I had not got a chance to show it to her. She could not read it, she was blind at the end, but my sister Carmel read parts of it to her. She read the opening paragraph, which was enough… And mammy saw me on the Late Late Show telling parents watching with their secretly gay children to tell them they loved them.” She says Derry was the ‘acid test’ – what would the reaction be of old neighbours, her mother’s friends. The Saturday after she had been on TV, she was in Derry for her mother’s 94th birthday. And in they all came, ”with in one hand a gift for my mum and in the other my book, asking me to sign it. I knew then it was OK.”

Another interesting thing about Nell is that it is dedicated to two nuns. It was a surprise to me that someone who has been so critical of the Church has such admiration for “holy women”. “I was blessed by them; two nuns who listened to me, showed me compassion, made it possible for me to go on when I was discovering what it meant to be gay. When I confessed to a priest that I was in love with another girl, he refused me absolution. I walked away and never went back to the Church after that day. But the nuns were gentle with me and I am full of gratitude for that. I was very religious growing up. It was what kept us going: we were God’s children. Protestants might have everything else but they would not go to heaven. It was real opium for the masses – and we believed that one day we would be free! I envy people now who have faith. In the lead up to my mam’s death, I can see how it is a comfort to people. And there is a lot of good sense in the Ten Commandments: give us today our daily bread – that phrase is people demanding their right; to be free from hunger; it is a civil rights demand. The holy men have just got in the way of the message of social justice. But I still have faith in the holy women”

The book is also a very personal, very intimate portrait of its author. Several chapters describe McCafferty’s relationship with Nuala O’Faolain, who McCafferty describes as “the love of her life”. Why did she feel it important to record it in such detail – and was she not worried about being so open about something so deeply personal? Does it not make her vulnerable? “No, not at all. I think that is what you do when you tell a love story – and I could not tell the story of my life without including it. I am more worried about what I did not include – I think there was much more to say! I wish I had captured more of the joy, more about our travels, things we did together. I am surprised when people ask me this – do they not think I had a domestic life, that I just walked around carrying placards all day? My only worry about this is whether I was fair to Nuala. I am not worried about saying I love someone. To me it is one of life’s greatest achievements. “

The last few months have clearly been difficult for McCafferty. She says she has not been able to sleep at night since December 16th – the day her mother died. Having spent the last four years caring for her mother, and also writing her book, a very disciplined life has given way to what she describes as “living in the twilight zone”. “I am glad though that I can take the time to absorb it. I have not really had a chance to talk or think much about what next. Right now I have no vision, no ambition, no objective. I am a woman in waiting. I am not usually very good at metaphors, but a friend of mine, Margaret McCurtain, does not say how are you – she always says “how does your garden grow?”, What I am thinking now is, I forgot to plant bulbs, I was busy doing other things – but sure something will come up in spring. I like figuring out problems, there is an answer to everything. But right now I have not got the energy to identify the problem. But I am sure that will come, in time".

0 comments:

Post a Comment