.

|

| Exclusive to the National Constitution Center's showing of 'Spies, Traitors, and Saboteurs,' visitors can view glass and granite fragments from the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, as well as a shoe that was recovered from the wreckage, on loan from the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum. (CAROL H. FEELY, CONTRIBUTED PHOTO / March 12, 2011 |

Twisted pieces of metal, salvaged from planes that struck the World Trade Center's twin towers in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001 are stark testimonials to the deadliest act of terrorism on American soil in the 21st century. But they're just one chapter of a larger story being told at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia.

"Spies, Traitors & Saboteurs: Fear and Freedom in America" details many more events and time periods in which Americans have been harmed by enemies within the country's borders. They range from a Revolutionary War plot to kidnap George Washington and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, to 1960s church bombings in the South and the Oklahoma City bombing.

The exhibition is not intended to make visitors afraid of their own shadows or suspicious of every person they meet. "We hope the exhibit will stimulate dialogue about how we can defend our country while also protecting the individual rights and freedoms that are at the heart of our democracy," says David Eisner, president and CEO of the Constitution Center.

The traveling exhibition, prepared by the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., explores stories of espionage and treason since the nation's birth and examines counter-intelligence measures that affect our daily lives.

"America changed forever on Sept. 11, 2001. The National Constitution Center is the perfect venue for a conversation about what wrenching and lasting change has come to mean to all of us," says the Spy Museum's Karen Corbin.

Those who explore the exhibition will rediscover the courage of first responders who ran toward the burning and collapsing twin towers. And they'll learn of other acts of courage in the face of terrorism, like Dolly Madison's efforts to save Washington's portrait from the burning White House when the nation's capital was under British attack in 1814.

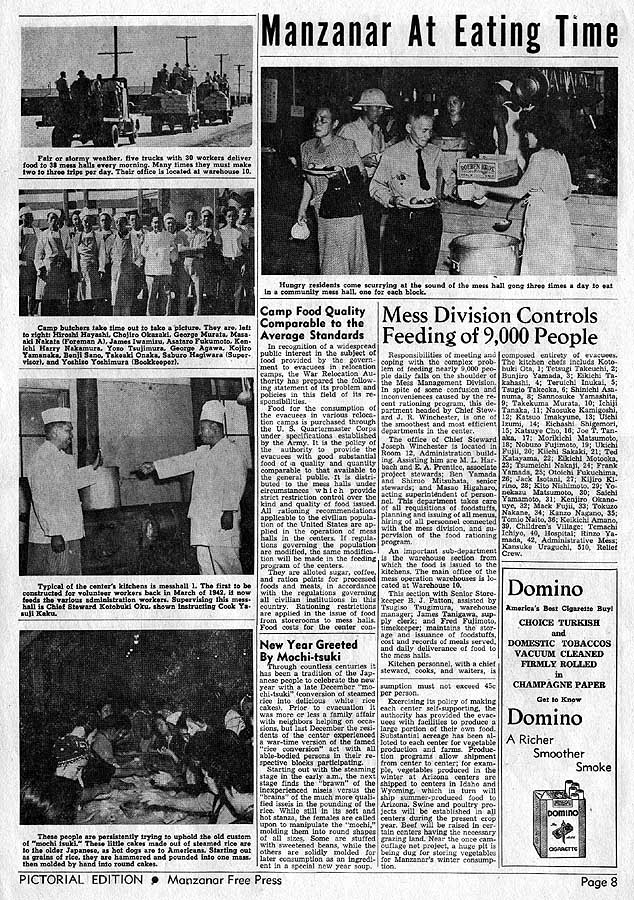

They'll also learn of less-than-admirable moments in our history, like the internment of Japanese Americans — which was triggered when a Japanese pilot returning from the Pearl Harbor attack crash-landed on the Hawaiian island of Niihau. With the help of a Japanese American, he took hostages and terrorized a community. According to the exhibit's information, "This incident perpetuated fears about Japanese Americans that ultimately led to the unprecedented incarceration of thousands."

Visitors also will have the chance to express opinions on questions raised in the exhibition about how the nation responded to events.

Using newspaper headlines, historic photographs, artifacts and video and themed room settings, the exhibition's timeline traces more than 80 acts of terror that have taken place in the United States from 1776 to the present.

One of the most intriguing incidents detailed in the exhibit is the account of the explosion at Black Tom Island in New York Harbor on July 30, 1916. "Although it is something people have forgotten about, the explosions at the island's munitions depot — triggered by German saboteurs at the outset of World War I — were felt as far away as Philadelphia. The response to that incident was the Espionage Act of 1917 that's still on the books today," says Steve Frank, staff historian for the Constitution Center.

He adds, "Some of the threats to national security have come from abroad, but others have been homegrown."

He points to the section dealing with the Ku Klux Klan — probably America's best-known terrorist organization. The section containing graphic proof of their shocking levels of violence, maybe something visitors with young children should skip. Its evolution from vigilante groups inflicting terror on former slaves after the Civil War to its position today as one of many white supremacist groups is a thought-provoking stop for adults and teens.

The exhibition is organized in nine segments: Revolution: 1776-1890; Sabotage, 1914-1918; Hate, 1865-present; Radicalism, 1917-1920; World War, 1935-1945; Subversion, 1945-1956; Protest, 1969-1976; Extremism, 1992-Present; Terrorism, 1980-Present.

Among artifacts and presentations found in the displays:

•Glass and granite fragments from the Alfred P. Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City and a shoe found in the wreckage.

•A ritual Ku Klux Klan red robe worn by the Klan "Kladd," who was the elected Klan officer presiding over secret rituals and ceremonies and KKK "business cards," which warned Americans that their every move was being watched.

•A badge and ID card carried in 1917 by an operative of the American Protective League who spied on fellow Americans on behalf of the U.S. Justice Department during World War I.

•A Weather Underground video presentation featuring an interview with ex-Weather Underground member Bernadine Dohrn.

•A replica of an anarchist's globe bomb that was presented as evidence in the 1886 trial of men tried in connection with the Chicago Haymarket riot.

There are designed "environments" too, like a militiaman's closet of weaponry and camouflage clothes, as well as a room set up like the 1950s office of an FBI agent. In the agent's office are file cabinets that can be opened to view the files kept on Americans who were suspected of being Communists, including Lucille Ball.

The beloved, red-headed comedienne apparently had registered to vote as a Communist in 1936 and again in 1938. As it turned out, she had done it only to please her grandfather. The ensuing investigation and interrogation by the House Committee for Un-American Activities failed to turn up anything more on Lucy. Observed her husband, Desi Arnaz, "The only thing red about Lucy is her hair, and even that's not legitimate."

By Diane W. Stoneback, OF THE MORNING CALL