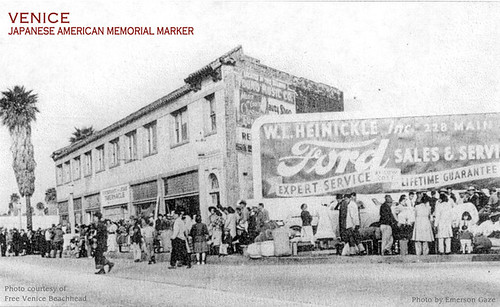

A memorial marker denoting the relocation of 1,000 local residents, including former Malibu resident Amy Ioki, to the Manzanar camp during World War II, will be placed at an intersection in Venice.

Amy Ioki was a member of the only Japanese American family in Malibu-and just 16 years old-when the call came to assemble at the corner of Lincoln and Venice boulevards in Venice, Calif. It was April 1942, four months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, when the United States entered the World War II stage as one of the Allied Big Three. Ioki's family, the Takahashis, was ordered to board the bus en route to the Manzanar War Relocation Authority Camp. It didn't matter that the high school junior, her two older brothers and three sisters were U.S. born; their crime was simply being Japanese.

“It was really like a concentration camp until they found out we were really harmless,” Ioki said.

Ioki, now 85, is one of the few surviving Southern California Japanese American citizens who will revisit next week, 69 years later, that fated intersection where 1,000 local residents who were removed from their homes were gathered and sent to the camp in Inyo County. The April 25 event, at 10 a.m., will be a groundbreaking for a memorial plaque to be located at the northwest corner of Venice and Lincoln. On the marker is an abbreviated synopsis of President Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 that allowed the U.S. government to declare the states of California, Oregon and Washington-at the time populated with more than 120,000 Japanese people-as “militarily sensitive” due to Pearl Harbor. Another command gave those families just days to dispose of their property and possessions, essentially forcing them to drop their lives.

“We lived in Malibu, I never felt any prejudice,” she said. “We all went on the same bus, day in and day out, and all became good friends.”

The trek to Manzanar, cramped in a dirty, stifled bus, poked and prodded through a round of vaccinations, was a far cry from the bucolic life in Malibu, where Ioki's parents were immigrant farmers from Yokohama. Luckily, because the Takahashis were a large family, they were placed in their own barrack, Block 23.

“If you were in a small family, they were put in a room with three other families,” Ioki said.

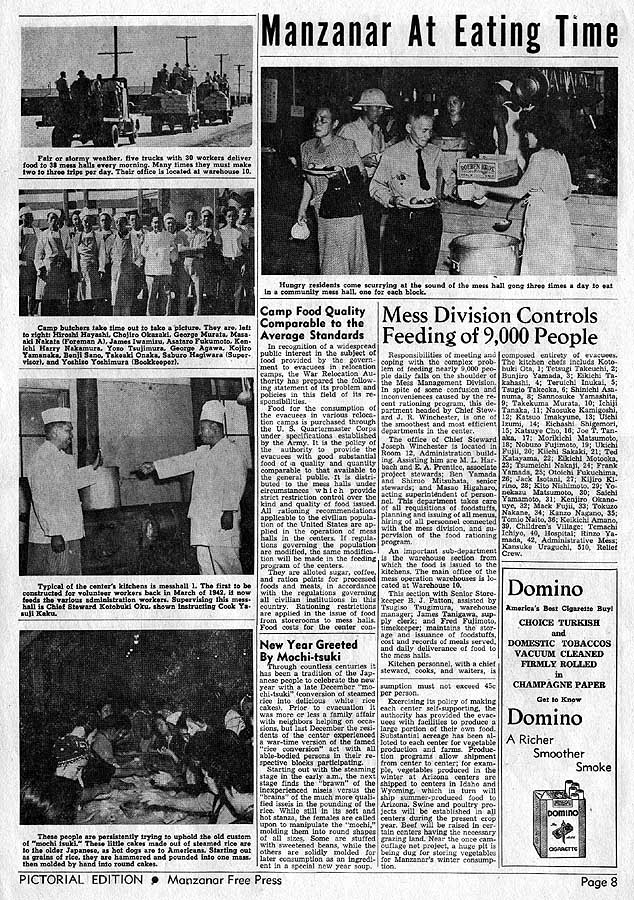

Overall conditions were poor: food consisted of tinned rations and school for the children consisted of hardly anything conducive to learning. It would remain that way for three years, until the end of the war.

“We sat on the floor and it was cold,” Ioki said. “No books, and the teachers were very young and probably just starting. Who would come out to a place like that if you were a good teacher?”

Their Japanese culture is what kept them going. Not long after being imprisoned, the internees found some solace through gardening and the arts. Ioki would go on to work in the camp hospital, which led to her later career path of medical stenography.

“When we were in camp, you had to make a life for yourself,” Ioki said, “because there were people from all phases of life, and the Japanese are for education, they had all kinds of classes.”

Ioki missed her high school graduation. And as she remained in the prison camp, her friends back in Malibu went off to attend Santa Monica City College or UCLA. Ioki credits her parents' strong resolve as survivors for getting them through the wartime period. “I think it's still part of the Japanese not to complain,” she said. “I never heard them complain about anything. We had to pick up everything and go. They never said a word, and my father never resented that they treated us differently. He never said anything against America. That's the mentality of the Japanese.” She continued, “Our folks were brought up that way; that we do as we're told.”

Though the connections came through tragedy, Ioki said she is grateful to have bonded with so many other Japanese during her time at Manzanar, like Mae Kakehashi, Arnold Maeda and Kazumi Tatsumi.

“We actually made many friends in camp. We stayed friends for 70 years now,” she said. “I guess we all had something in common. Everybody was the same. Everybody lived in a barrack. After we were released and we'd meet another Japanese, they'd ask, ‘What camp were you in?' The conversation would start there.

An ad-hoc group, VJAMM, the Venice Japanese Memorial Marker Committee, was formed specifically to create and place the memorial at the Venice street corner. The pedestal and accompanying plaque's design of suitcases and luggage, created by artist Emily Winters, symbolize, in part, the sudden displacement of the Japanese that day in April 1942.

VJAMM member Suzanne Thompson, also a co-founder of the Venice Arts Council, said the project originated through Venice High School teacher Phyllis Hayashibara, whose students reached out to Los Angeles District 11 Council Member Bill Rosendahl. Rosendahl became interested in the project, Thompson said, and took the steps to obtain permits for the memorial's construction, and also fronted $5,000 for the project. VJAMM has also raised about $2,500, but still needs $15,000 more to cover all expenses. Both the Venice Community Housing Corporation and the arts council are overseeing the donation fund.

After being released from Manzanar, Ioki, who now lives in Mar Vista, later married and had four children, who all graduated from UCLA. Ioki's husband died last year. Ioki said the marker is special for her because it pays respect to her parents and all the Japanese mothers and fathers who were forced to uproot their families.

“I think it's a nice thing for people because they had a lot of Japanese farmers. It would be a nice thing for them all to be remembered like that,” she said. “We don't want something like this to happen again.”

Contributions toward the memorial marker can be made to the VCHC/VAC (“VJAMM” in the memo section of personal checks) and mailed to the Venice Arts Council/VJAMM, P.O. Box 993, Venice, CA 90294. More information can be obtained by calling 310.570.5419 or online at www.venicejamm.org

Reprint from The Malibu Times; By Paul Sisolak / Special to The Malibu Times