SANTA FE, N.M. — One entrepreneur ran a gambling den beneath the camp barracks. Another published a newspaper called the Santa Fe Times. Some men brewed sake. Others grew their own vegetables to trade for meat with the hospital and the state penitentiary.

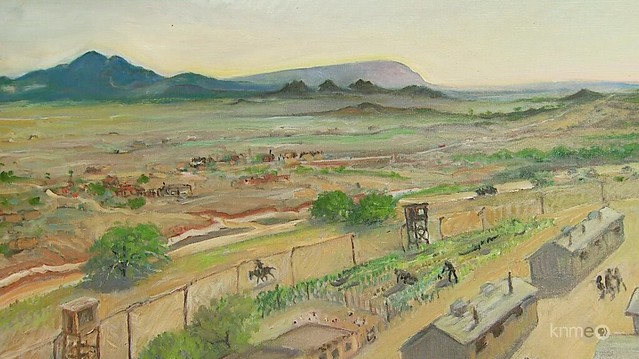

During World War II, the U.S. government detained more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent in internment camps spread throughout the West. From 1942 to 1946, the Santa Fe camp held 4,500 of those men behind barbed wire at a site two miles from the Plaza in what is now the Casa Solana neighborhood. The Department of Justice and the FBI labeled them "the worst of the worst." Educated and successful leaders, they were powerful men whom officials deemed the most likely able to assist the enemy if they chose to, Simon said.

Neil Simon's DVD "Prisoners and Patriots: The Untold Story ofJapanese Internment in Santa Fe" is the first documentary to fill the void of silence surrounding the World War II incarceration of Buddhist ministers, businessmen, teachers and journalists from the West Coast, Hawaii and Latin America in New Mexico. A journalist who worked for KOB-TV in Albuquerque as well as in stints in El Paso and in Washington, D.C., Simon has based the film on 20 hours of exclusive interviews with Santa Fe survivors and their families, previously classified government documents and private photographs.

It's a story many fathers never told their own children. Some of the prisoners recalled the cruel irony of being locked up at the camp while their sons donned U.S. Army uniforms. Simon will screen the movie at the Museum of International Folk Art on Sept. 9. In the meantime, the DVD is available at http://www.kickstarter.com/projects.

Now working for the 56-country Organization for Security and Cooperation, Simon learned about the New Mexico camp while he was working as a journalist in Albuquerque but could find no information about it. Awarded a congressional fellowship in 2002, he assumed he could research the subject at the National Archives and the Library of Congress.

"When I did that, I realized there was nothing," he said in a telephone interview from Kazakhstan, where he was overseeing parliamentary elections.

Simon started scouring the Internet for camp artifacts and reunion yearbooks on eBay. He discovered a photographer had posted photographs online on Flickr, then traced her to a California Japanese calligraphy class. Two women in the class were the children of survivors.

That connection led to Bill Nishimura, who was interned in Santa Fe for being a member of the pro-Japanese group Hoshi Dan in Tule Lake, Calif., and for declining to answer the government's loyalty questionnaire. Nishimura was the only surviving Santa Fe internee to speak at the site during the 2002 dedication of the historic monument at the camp.

Simon estimates that about 20 camp veterans are still alive. He talked to five of them and their families, including the son of the camp doctor.

He fully expected to encounter bitterness and resentment when he talked to the survivors. He discovered the opposite.

"They had a good time," he said. "They played baseball. They brewed sake; they grew vegetables. They did wood carving and stone polishing. They did acting."

Although some have traced their post-camp silence to shame, Simon credits it to a traditional Japanese term called "shouganai."

"It means letting it roll off the body," he said. "It's, 'Let's move on; let's not hold a grudge.' "

"I think he must have said 10 times, 'Take it as it comes,' " Simon said. "He never was an ambitious man after his camp experience. His daughter was very sad about his whole life. But you got from him this sense of honor and a lack of bitterness."

The men didn't want to burden themselves or their families, he added.

Nishimura spoke of "playing baseball and ogling women when they rode their horses past the camp," Simon said. "One started a gambling ring under his cabin. He had a whole gambling thing going on. There was a poetry club. And they did some hiking."

At just 19, Norman Hirose was likely the youngest man in the camp. He was incarcerated with his family first at Tanforan (San Francisco) then at Topaz, Utah, after asserting "no, no" on the loyalty questionnaire asking whether he would foreswear allegiance to Japan and serve in the U.S. armed forces. The government shipped him to Santa Fe in 1946, telling him he would go back to Japan soon.

"You really got the sense that he was excited and proud," Simon said. "He looked forward to the internment experience, because it was something new."

Aside from being stripped of their civil rights and separated from their families, most of the men said they had been treated well, although Simon documented "two or three" instances of negative treatment from the camp guards.

"Some would curse at them," he said.

Some detainees retained their loyalty to Japan by wearing the Rising Sun symbol on their clothing. Members of the Hoshi Dan, a pro-Japanese movement that grew out of California, were considered troublemakers and shipped to Santa Fe.

"They did military-style exercises," Simon said. "Everyone knew if you were moved to Santa Fe — that was about as low as you could go."

A small riot erupted after a guard tossed tear gas at a prisoner and billy clubs appeared. Officials gloated about keeping the incident out of the press, he added. "A few people went to the hospital."

Camp members were allowed to send and receive mail, but much of it was censored. "There are a lot of letters," Simon said. "A lot of folks said a whole letter would be cut out. This was very routine."

Seichi "Sam" Yamakawa, who died in 2011, was shipped to Santa Fefor stating in hearings that he would not serve in the U.S. Army and planned to repatriate to Japan to care for his mother. After the war, he returned to California only to find people from Oklahoma had moved West and taken over his family farmland.

"I think he must have said 10 times, 'Take it as it comes,' " Simon said. "He never was an ambitious man after his camp experience. His daughter was very sad about his whole life. But you got from him this sense of honor and a lack of bitterness."

"I went into this project thinking every interview would be the same — denigrating the U.S. government and parallels to 9/11," he added. "And to a man, it was the opposite."

0 comments:

Post a Comment