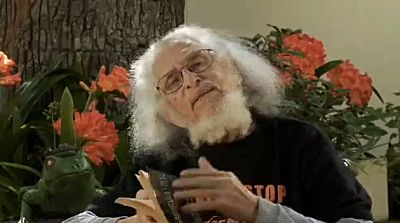

Denis Brutus, (28 November 1924 – 26 December 2009) born in 1924 in what was then British Rhodesia to South African parents, shot to prominence (and jail) in the 1960s campaigning for a boycott of South Africa in the sporting world. A veteran activist, poet and Professor of African Studies and African Literature, Brutus continues to campaign vigorously against economic injustice. His targets today are the corporations, banks and institutions that profit from what he terms a “global system of economic apartheid”. Robert Looby recently had the pleasure of discussing the past, present and future with Prof. Brutus

How did you get involved in the struggle for justice?

I grew up in a segregated area of course. I'm classified as a non-white or a coloured, so one is exposed to racial segregation very early, and remember this is the twenties and the thirties when I grew up. But I always make the point that within a community one is protected from the kind of harsh racism that one would experience outside that community. We were one of the early creations of what was called the segregation policy, which later became the apartheid policy of course, from 1948 onwards, when the apartheid government was elected. In the ’20s and the ’30s you had a kind of colonial racism not unlike what was happening in the south of the United States, where schools and churches were separated for black and white. In South Africa eventually they would have post offices with separate entrances for black and white or, as it was called, white and non-white. (Blacks were divided into fairly broad categories under the term ‘non-white’.) There were buses for whites only and buses for non-whites.

Above all that you need to internationalise the pressures… if they're globalising oppression, we are globalising resistance.

So I grow up in that context, but I'm not particularly aware of it because, as I say, one is sheltered. When I start going to school and later to high school and I have to travel through the city – then of course one becomes more aware of the signs that say ,whites only, or ,non-whites only’, although the language they used was ‘Europeans’ and ‘non-Europeans’ so that amusingly people coming from America for instance thought that they ought to get into a non-white bus. They were not Europeans; they were Americans. It's one of those minor confusions.

Once I went to high school, one became more aware of the racial discrimination between white and non-white in the bus service and of course always the bad service was for the non-whites. I think it was actually at university that it really came home to me, although I'd been aware of it at high school. And it came to me in a peculiar way. I went to a black college called Fort Hare, which had been an old military outpost commanded by a colonel called Hare in the days of the colonial wars against the Africans. Then this fort was taken over by the churches as a kind of ecumenical enterprise and jointly they put up a college for non-whites – blacks actually – and it was named after Fort Hare. One of the things that struck me was that some of the best athletes in the country were at Fort Hare and they were performing better than any white athletes in that particular sport, but they were not allowed to be on the Olympic team because the government proudly announced that there would never be a black on the Olympic team.

It gets a little more complicated because according to the Olympics you ought to select on merit and not penalise people because of their race, so I became involved in opposing the policy of racism and apartheid essentially from a sports angle initially. Now amusingly, people have paid me the compliment of saying I was very smart to select sport as the area in which the apartheid system was vulnerable, but in fact I didn't tackle the system because I thought it was vulnerable at that point. I just thought it was plain unfair to keep athletes off the team because of their colour; so you can see how I eventually collide with the system and I'm banned and I'm arrested and put under house arrest and jailed and I escape and I get shot in the back in Johannesburg and I end up on Robben island with Nelson Mandela in the same section of the prison, breaking stones. But it really began with sport, and I feel I ought to say this. I don't want to get credit for something I don't deserve: being some very smart guy who took on apartheid via sport. That was not my approach. My approach was: I took on sport as racism and in the process found myself in conflict with the apartheid system …

What lessons are there to be learned from the defeat of apartheid?

Above all that you need to internationalise the pressures – and it helps to have specific targets. The springbok rugby team created one for us; Barclays Bank may offer us the same opportunity – they operate in more than 80 countries. When I was in Britain, together with Peter Hain, now a member of the Tony Blair government, I organised a very effective campaign all across Barclays banks and eventually, as you may know, we forced them to leave South Africa. They're now returning in spite of having been one of the big allies of apartheid so we are mobilising opposition to them. What is important about it is that Barclays operates in more than 80 countries all over the world. We're planning to organise protests in all 80 of those countries so if they're globalising oppression, we are globalising resistance.

I was in court earlier this month in Johannesburg opposing the takeover of the biggest retailing bank in South Africa, ABSA (Amalgamated Bank of South Africa – the bank with the widest services among the popular masses), by Barclays Bank. You must remember that Barclays was one of the banks that financed the apartheid system and lent it enormous sums even when the UN was condemning the system and calling for a boycott. The campaign is still on.

With the collapse of apartheid were you not tempted to retire from public life and leave others to carry on the struggle for justice?

I wish I could say yes, but unfortunately I went back to South Africa, largely at Mandela's invitation, at the time of his triumph in the elections. The ANC was unbanned and they had a celebration. And I realised that the ANC had made a deal with white power so that in fact corporations were still going to run the system. They were still going to own the gold and the banks and they were also going to run the Olympic committee. It was operated by whites even though the whole fight had been about trying to get a more representative structure. But the ANC, perhaps in its anxiety to get power – and many of them of course were compromisers secretly – undertook various negotiations. The ANC had in fact sent young men and women to train with the World Bank as interns, so clearly they were not interested so much in changing the system as changing who ran the system. When I realised that, I understood, really reluctantly, that the fight wasn't over and that I would simply have to keep going. When I got back they said to me at the airport: 'How does it feel to be back in a democracy now?' And I said 'Hold it, hold it. I don't think we've arrived in a democracy yet.' So I was unpopular of course because clearly I was saying things that people would rather I did not.

You were also in Edinburgh for the G8 meeting. What did you achieve there?

It is helpful to focus on current events. Edinburgh and the G8 Summit was a major advance for us and a major setback for our opponents. Blair's attempt to distract attention from the war in Iraq, the anger of the British people at his lies, and his pusillanimous following of the bushcowboy-rampaging – all failures; anger against the war and his conduct was, instead, intensified. And his hijacking of a major section of civil society, by lining up NGOs around white whatevers and claptrap about Making Poverty History also backfired; more people in Britain and the world understand better the essential cruelty and rapacity of a global economic system – global economic apartheid – which exploits and crushes millions around the world.

For us, I think, our greatest gains were in mobilising and organising radical voices on one of Britain's great historic occasions, and in turning around the pleas for pity and charity so that they became strident demands for social justice. Political awareness, in Britain and around the world, benefited greatly. Our thanks to all those who organised so well and so generously.

The larger fight, of course, continues. And so in Africa we are still struggling to beat back the imperialist designs of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), just as the people of the Americas are fighting CAFTA as their contribution to our global struggle. Overall, I believe we are steadily making advances.

The Bonos and the Geldofs confuse the issue for many, who then believe the problems can be solved by charity. For a contrary opinion, seeMonbiot. They failed to persuade many at the G8, so we can keep going. We may even have gained momentum, since many more now have a better understanding of the problem.

George Monbiot has spoken to us about the &ldquoconditionalities” attached to debt relief programmes.

The tricky thing is that conditionalities vary from country to country. Countries that are given loans generally have three conditionalities imposed on them. Many others, but principally three. One: they are forced to accept an SAP, or Structural Adjustment Programme, which requires the countries to change the whole structure of their economies. They have to put the focus on export, producing for export and going to export markets. That means several things. One is of course that when you are producing corn for export, you don't have corn for local consumption. You literally are starving the people at home by aiming at getting to the market. Point two is that you're at the mercy of the market and you often have to sell at the market price, which really is a price that does not give you a very good return on your economy, but the fact that you are producing goods for export, not for local consumption, is more serious. Why do they insist on that? There are many reasons but I'll give you just one. When loans are given to developing countries by the western countries, they are given in dollars and must be repaid in dollars. This means that you have to earn dollars and the way you earn dollars is by going to the export market and getting foreign currency. That's one of the conditionalities.

Another one, much more serious in my view, although they're all serious, is that the World Bank and the other external banks become what are called &ldquopriority creditors” and this means that you have to repay them or at least pay a service on the debt. But because they're a priority creditor social services at home – whether schools, hospitals, water, housing, roads, infrastructure – all have to wait until you have paid your debt or your service on the debt. This means a tremendous burden on the people because they are not getting the services they should and the money that comes in as taxation goes out as service on the debt. Social services are therefore desperately neglected all over what we call the global south – countries in Africa and Asia and South America, who are all victims of this burden of debt. By the latest count it is about 180 countries and the total debt is in the region of – if you use English figures – 2,000 billion1. So the second one is this loss of social services because your money is going on the repayment of debt.

The third conditionality varies from country to country but is probably the worst: in order to qualify for debt forgiveness or even partial debt forgiveness or some kind of phoney debt forgiveness where they lend you the money to pay them what you owe, incurring a new debt in place of the old one, i.e. to become what is called a HIPC, or Highly Indebted Poor Country, you have to make a firm and binding commitment that you will take orders from the World Bank and the IMF. If you don't, you are guilty of what is called &ldquobad governance” as opposed to &ldquogood governance” so you virtually sign a death warrant. This is a new form of enslavement and has been correctly so described by the African Council of Churches and others. By making that binding commitment to obey the orders, prescriptions and conditionalities of the World Bank and the IMF, you are virtually being recolonised, being re-enslaved by the chains of debt.

How are you maintaining the pressure?

Increased education is what keeps us going – and growing; this is how, eventually we won the South Africa fight. Now we have better resources, but more powerful forces against us, such as consumerism, which distracts the young we might recruit. But we keep growing – in South Africa, but also in South America.

We're really going after not only all the banks, but the World Bank and the IMF. So it's a very broad picture. In that picture, what we specifically do with Barclays is really up to my campaign and the strategies developed. Let me give you the three current strategies. One strategy is to demand an apology from Barclays for its guilt in financing the apartheid system. We want a public apology for that. Point two: we want reparations to be paid to the victims of apartheid. There are many still who have never received any assistance from the government in spite of the fact that there was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as you remember. There were recommendations that certain sums of money should be given to the victims of apartheid and they've never got those monies. Point three is a rather complicated one. We have filed a law suit in the New York Supreme Court naming 23 corporations and demanding reparations from them. Barclays is one of the 23, so we're saying Barclays should not enter South Africa – although the government has okayed it – until the lawsuit in the New York Supreme Court is resolved.

Right now I'm quite excited about three projects for which we’re not getting any support, though that doesn't deter me. We'll probably get them done eventually. One is we're trying to have a conference in the US in which we will combine Africans and African Americans on the issue of reparations. They're both campaigning on the issue of reparations but they campaign separately. We’re trying to pool them together so for me that's quite a demanding project because it would involve hundreds of people if we can pull it off. And two: we’re planning an action in South Africa where the victims of apartheid will confront the minister in the parliament building itself. There'll be a march on parliament and a demand that the government take action to deliver on reparations and that too will take some time. Also, I've a new book coming out, early next year. I've just had one come out, a collection of poetry called Leaf Drift. It's a kind of mixture – just leaves, drifting together. So I'm kept busy. I turned 80 last year and I might turn 81 this year if I last long enough. There's enough to keep me busy.

Notes

1 A figure of $2.5 trillion is given by George Monbiot in his The Age of

Consent (2003) after Romilly Greenhill and Ann Pettifor, The United States

as an HIPC (Highly Indebted Poor Country) – how the Poor are Financing the

Rich

More about Dennis Brutus: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dennis_Brutus

reference: http://www.threemonkeysonline.com/still-fighting-apartheid-south-african-activist-dennis-brutus/1/

Published collections

- Sirens Knuckles and Boots (Mbari Productions, 1963).

- Letters to Martha and Other Poems from a South African Prison (Heinemann, 1968).

- Poems from Algiers (African and Afro-American Studies and Research Institute, 1970).

- A Simple Lust (Heinemann, 1973).

- China Poems (African and Afro-American studies and Research Centre, 1975).

- Stubborn Hope (Three Continents Press/Heinemann, 1978).

- Salutes and Censures (Fourth Dimension, 1982).

- Airs & Tributes (Whirlwind Press, 1989).

- Still the Sirens (Pennywhistle Press, 1993).

- Remembering Soweto, ed. Lamont B. Steptoe (Whirlwind Press, 2004).

- Leafdrift, ed. Lamont B. Steptoe (Whirlwind Press, 2005).

- Poetry and Protest: A Dennis Brutus Reader (Haymarket Books, 2006).

0 comments:

Post a Comment