Manzanar: Telling the Story (Reprint from 2011)

By MARTHA NAKAGAWA

RAFU CONTRIBUTOR

Manzanar: Telling the Story (Reprint from 2011)

By MARTHA NAKAGAWA

RAFU CONTRIBUTOR

More than 1,100 people of all ages gather for 42nd annual Manzanar PilgrimageCamp inmates return and share their experiences in Manzanar.

More than 1,100 people attended the 42nd annual Manzanar Pilgrimage held on April 30, with attendees coming as far away as Japan, Europe and Africa, and ages ranging from those still in the single digits to 95-year-old Jack Kunitomi, brother of the late Sue Kunitomi Embrey, who led the charge to make the former American concentration camp into the Manzanar National Historic Site.

Mary Kageyama Nomura, known as the “Songbird of Manzanar,” continued to wow a new generation of students as she sang “The Manzanar Song,” written by the late Louis Frizzell, a music teacher at Manzanar.

Darrell Kunitomi, the emcee, encouraged participants to share their experiences with others when they returned home.

“If you don’t tell the story, the story will die,” said Kunitomi.

This year’s theme focused on champions of civil rights and those profiled included Frank Emi, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, William Hohri and Fred Korematsu.

John Esaki and Amy Kato also screened the docu-drama “Stand up for Justice,” which recounts the story of Ralph Lazo, a Mexican American who entered Manzanar with his Nikkei friends.

Keynote Speech

Mako Nakagawa from Seattle gave the keynote speech. During World War II, she was incarcerated at the Puyallup Assembly Center in Washington, the Minidoka WRA camp in Idaho, and then theDepartment of Justice camp at Crystal City in Texas.

Nakagawa is credited with spearheading the successful passage of the “Power of Words” resolution at the 2010 National JACL (Japanese American Citizens League) Convention. The resolution, which passed with 80 chapters supporting and two chapters dissenting, authorizes the formation of a committee to promote the usage of correct terminology, rather than euphemisms to describe the wartime camp experience.

Nakagawa has garnered support from this year’s Sue Kunitomi Embrey Legacy Award honoree Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, author of “Words Can Lie or Clarify: Terminology of the World War II Incarceration of Japanese Americans.”

The resolution gives a list of words to replace current euphemisms. Among them is replacing such terms as “internment camps” or “relocation camps” with “American concentration camps.”

Nakagawa said despite some controversy the resolution passed by a wide margin. But she was aware that the battle was not over yet and encouraged attendees, especially the younger generation, to become active.

“What can you do?” Nakagawa asked rhetorically. “For starters, you can do a lot for JACL. Commend the National Council for the vote on the ‘Power of Words’ resolution that passed by such a landslide. Discuss with your family and friends the issue of euphemism and their role in promoting misinformation and nonsense propaganda. Write articles and letters. Do not shy away from the term ‘concentration camps.’ Read more. Give the literature on terminology a fair hearing. Encourage all the organizations you’re connected with to switch from terms considered euphemisms and misnomers, and adopt terms that are much more accurate and describe the truth in history.”

NPS

“What’s encouraging is seeing so many young people here,” said Lee. “I love the fact that there are students here from Pasadena City College and UCLA, USC and Cal Poly Pomona. And there clearly are generations here, grandparents with their grandchildren. That’s an exciting thing to see.”Martha Lee, deputy regional director for the National Park Service’s Pacific West region, was among those in attendance. She was not visiting on official capacity. Tom Leatherman, former Manzanar superintendent, who now works under Lee, had encouraged her to attend a pilgrimage.

Lee was very familiar with the Manzanar story. “I grew up in Southern California, in Pasadena, and my parents were huge civil rights activists,” she said. “It was a story I grew up knowing. A lot of the kids in my public school in Pasadena were Japanese Americans and their parents lived this.”

While living in Yosemite during the 1970s, Lee made a trip to the Owens Valley specifically to locate Manzanar.

“I knew the story of Manzanar and came down to find the site and to walk around it,” said Lee. “My very first time I came out here, I felt incredibly moved by this place. I felt some power here.”

Lee, who worked at the Kalaupapa National Historic Park in Hawaii, drew parallels to what happened to the lepers and to what had happened to the Nikkei.

“This gut reaction of isolating people is from ignorance and from fear,” Lee said. “I just think we have this great potential here. This is one of those places where we can pause and remember and recommit ourselves as Americans, to make sure that America is a place where we all have equal opportunities and are treated equally.”

Manzanar Superintendent Les Inafuku had a chance to take Lee out to the former Manzanar reservoir site, which is under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Earlier this year, Inafuku and Manzanar archeologist Jeff Burton had given a tour of the reservoir to the newly appointed BLM field manager and discussed with the BLM’s state officer the possibility of a land exchange so that the reservoir would come under NPS jurisdiction. Lee promised Inafuku that she would contact the BLM.

Inafuku was optimistic that the reservoir, which has a number of former camp inmate names and messages etched into the cement, will one day be turned over to the NPS.

But while the Manzanar staff continues to pursue various projects, Inafuku is worried that the federal government’s budget woes will have an impact in fiscal year 2012. If it is a drastic cut, he dreads having to consider cutting back on staff.

“It’s really going to be tough,” said Inafuku.

AWARDEES

The Sue Kunitomi Embrey Legacy Award, unofficially known as the “Baka Guts” Award, was given to Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga. Rose Ochi accepted on behalf of Herzig-Yoshinaga, who could not make the trip.

“Aiko is really an incredible example of how one person, through their dedication and hard work, could actually rewrite history,” said Ochi. “But her pivotal contributions have been pretty much hidden… but Aiko is someone who has toiled behind the scenes in the National Archives to really discover the smoking gun.

“She found evidence of lies. She did this wonderful detective work and found not only information that our government was aware there was no military necessity in rounding up Japanese Americans, but she also uncovered the efforts to bury that information. So she developed critical information that was essential for the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians’ report, which led to the efforts of the Japanese American community and their friends for the passage of the redress legislation.”

Also in attendance was last year’s Legacy Award honoree, Bill Michael, who, as former director of the Eastern California Museum, bore the brunt of the local Inyo County residents’ misdirected anger during the Manzanar Committee’s decades-long struggle to get the former campsite designated as a national historic site.

Manzanar Committee Co-Chairs Kerry Cababa and Bruce Embrey presented special recognition awards to Mo Nishida, Richard Potashin and Alisa Lynch.

Nishida was honored for organizing the 50/500 run from Los Angeles to Manzanar for the past 20 years.

“Every year, Mo organizes and leads a relay run that goes from Los Angeles to Manzanar,” said Cababa. “And they always arrive at the pilgrimage without fail. Along the way, they’ve had tragedies and accidents, but Mo has been so faithful to this whole pilgrimage.”

Nishida, a former Manzanar inmate, said, “The reason why we run, of course, is to honor our ancestors and memorialize the experiences of our people here.”

The other two honorees, Potashin and Lynch, are the longest-serving staff members at Manzanar. Lynch will observe her 10th year anniversary in September but Potashin will soon be leaving to Northern California where his wife, Nancy Hadlock, will be working at the Lava Beds National Monument, which oversees the Tule Lake campsite.

Lynch credited the entire MNHS staff for the park’s success. “I’ve just been here the longest, but we have 16 people on staff here who work very hard and who are a part of everything that we do here,” she said.

“I used to work at Independence Hall, where they have the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence and the Liberty Bell. And people used to ask me, ‘What is a park ranger doing here in the city?’ People assume that park rangers are only at Yellowstone or Yosemite or the Grand Canyon, but actually our National Park Service has 394 sites, most of those sites are historic and cultural sites. There are a lot places like the Tuskegee Airmen, Ellis Island, the Statue of Liberty, women’s rights sites, so we are very proud, all of us at the National Park Service, to also have these amazing civil rights sites, which hopefully will remind us never again.”

Potashin could not attend the ceremony as he was leading a group tour.

Former Manzanar inmate Ben Ogami, 85, came from Africa to attend the 42nd annual Manzanar Pilgrimage held on April 30.

“It feels like I’m coming home,” said Ogami, who retired in Africa after helping another former Manzanar inmate, Dr. Gordon Sato, on the Manzanar Project in Eritrea.

Sato, an award-winning cell biologist, had created the Manzanar Project to try to curb world hunger, utilizing a low-tech aquaculture method of combining sewage and other wastes to feed brine shrimp, which in turn would feed larger fish. Marine life is nurtured among the mangrove trees, which grow in coastal salt waters.

Ogami met Sato in Manzanar but the two took different paths before hooking up again. During the war, Ogami’s parents saw no hope for the family in the U.S. and insisted they go to Japan, over the objections of American-born Ogami and his brother Arthur.Sato brought the concept to Eritrea, which, at the time, was fighting for independence from Ethiopia.

From Manzanar, the family went to the Tule Lake Segregation Center. The brothers were then sent to the Department of Justice camp in Bismarck, N.D., before the entire family was shipped to Japan in December 1945.

This year, Ogami was brought to the pilgrimage by his nephew, Eugene Ogami, who was born in Japan but was given U.S. citizenship through his father’s work connections with the U.S. occupation forces. Eugene’s father also had his U.S. citizenship restored earlier than most, while Ben went through attorney Wayne Collins.

For Eugene’s father, a 2010 return to Bismarck marked a turning point. “I think he felt that it was a closure, starting with his internment at Manzanar all the way to his deportation to Japan,” said Eugene. “Going back to Bismarck and Fort Lincoln and being ceremoniously healed by the tribal Indians got him very emotional.”

George and Yoshie Kitayama Moriyama had lived in Florin, Sacramento County, before the war. They were sent to the Fresno Assembly Center and then to the Jerome WRA camp in Arkansas before ending up at Tule Lake.

One bright spot at Tule Lake was that the two married there, with Rev. Odate officiating.

George said he came to the Manzanar Pilgrimage because some of the Florin Nikkei had been sent to Manzanar.

“A lot of people from Florin were sent to Manzanar,” said George. “My uncle came here so I wanted to see what this place looked like. I guess it’s all the same. The barracks are the same but it is picturesque compared to Tule Lake.”

As an Issei, George did not have to renounce his American citizenship, but his wife did renounce.

“I was the only one in the family to renounce,” said the wife. “I wasn’t angry but it was to keep the family together.”

Like George Moriyama, Mitsuo Yamamoto had attended the Manzanar Pilgrimage to see how his friends had lived. Yamamoto lived in Elk Grove before the war and was sent to the Jerome and Gila River WRA camps.

“From where I lived in Elk Grove, about half a mile or a quarter of a mile on one side — those people were sent to Manzanar,” said Yamamoto. “We were sent to the Fresno Assembly Center, so I don’t know how they determined which families go where.

“Some of my friends came here, so I was kind of curious to see what Manzanar is like. I’m really impressed with all the displays here.”

Harry Honda, Pacific Citizen’s editor emeritus, first visited Manzanar in 1943. “I was in the service and they weren’t allowing Nisei soldiers to come back to the West Coast,” he said. “They didn’t want the Nisei soldiers to be confusing the MPs (military police), so they kept us out.

“My thing was that I wanted to come back and pack up our things so my folks can evacuate, but I couldn’t come out here to help them. But after ’43, they allowed us to return, so you see a lot of pictures of Nisei soldiers in camp — those were taken after ’43.”

Although Barbara Kato Shirota, a former Heart Mountain (Wyo.) camp inmate, had stopped by Manzanar on her own a few times, this was her first pilgrimage. She was surprised by the number of people and the work put into the site by NPS.Honda’s parents were sent to Rohwer but Honda, who lived Los Angeles before the war, made a trip to Manzanar to see his friends. “I came out here in ‘43 and stayed at Maryknoll (Japanese Catholic Center), at the rectory, and that’s how I was able to look around J-Town. At that time, it was all Bronzeville (African American community).”

“When we came, it was just the plaque at the guard shack and the auditorium that CalTrans was using,” said Kato Shirota. “Now the blocks are numbered so you can kind of visualize the barracks…We may have to come back on our own so we can see everything at a leisurely pace.”

Kato Shirota was just turning 10 when she entered Heart Mountain. Her memories of camp were positive ones such as learning to ice skate on the frozen pond or playing baseball.

“Another thing I remember is (Army Air Corps gunner) Ben Kuroki coming to camp,” said Kato Shirota. “I was in the Girls Scouts, so we were in the parade.”

Kato Shirota’s husband, Jon, is the award-winning author and playwright from Hawaii. Although Hawaii had a large Nikkei population, the islands did not undergo mass Nikkei imprisonment, largely from fear that the Hawaiian economy would collapse. Jon, however, was encouraged that the NPS was leading the effort to preserve several camps such as on Sand Island and Honouliuli.

“You know, if you can forget about the camp days and just look at this scenery, it’s a beautiful place,” said Jon. “But then, how can you forget about the camp days? Then it becomes sad.”

Fumie Ishii Shimada and her family were never in camp during the war. Her father worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad in Nevada, which was outside the restricted military zone for Nikkei. But during the war, Ishii Shimada’s father was fired and had a difficult time providing for the family.

“Because my father was fired and we had five children in our family, my mother asked to go into camp, but they said no because we were not from the West Coast,” said Ishii Shimada. “And there was a certain period when my dad wasn’t allowed to work. I don’t know why.

“That meant my oldest brother, who was a senior in high school, and my sister, who was a junior, had to go out to work to help support the family. And my mother did work for different farms, and my other brother did odd jobs.”

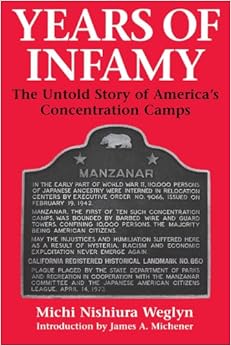

She credits people like Andy Russell and “Years of Infamy” author Michi Weglyn in helping to get Nikkei railroad and mine workers reparations. She also appreciated that the Los Angeles chapter of Nikkei for Civil Rights and Reparations (then known as National Coalition for Redress and Reparations) had sponsored her trip to Washington, D.C. to discuss the issue with Bill Lann Lee, then assistant attorney general for the U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division.

IR (Council on American-Islamic Relations), which has been sending hundreds of students from Northern California, Los Angeles and San Diego .

The San Diego group, which had a large Somali American contingent, came in two buses: one for the females and another for the males.

Suluy Abdirahmam, who attends both San Diego State and City College , was born in Somalia and arrived in the U.S. just after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks.

“It was a little hard,” said Abdirahmam. “People didn’t like us. Everybody thought that a person with a hijab had a bomb underneath it. It was just crazy.”

This was Abdhirahmam’s first visit to Manzanar. She was not aware that the U.S. had concentration camps before making the trip. However, although she did not want to diminish the hardships at Manzanar, she noted that it was nothing compared to what was happening in her homeland.In high school, Abdhirahmam said other students would sometimes harass her, calling her names and telling her to “go back home.”

“When we had the war back home, we had it much worse,” said Abdirahmam. “At least the people here had food and a place to sleep. Back home, I know the country is getting better, but it was a disaster. So I guess seeing the things here was not very shocking to me because I’ve seen worse.”

Abdirahmam plans to finish school so she can return to her homeland and open a school. “I really want to go home because there is nothing like home,” she said.

Aisha Basheer, an Arroyo Paseo Charter High School student, was born in the U.S. to Somali immigrant parents.

“I didn’t know we had concentration camps for the Japanese people in California or in the United States, so I wanted to see one,” said Basheer, who upon arriving at Manzanar felt “really sad.”

Basheer said she plans to encourage other family members to attend next year’s pilgrimage.

Fatha Ali, a Mesa College student, has been living in the U.S. for the past five years. She came from Kenya but her family is originally from Somalia.

“It was very beneficial coming today,” said Ali. “Learning about what happened to the Japanese people here has been educational.”

For Nida Asalm and Myra Mughal, students at Fountain Valley High School, this was their second trip.Like Abdirahmam, Ali hopes to finish her education and return to her homeland.

“It’s kind of eerie to think that things that were here were completely demolished because they wanted to get rid of any traces of it,” said Asalm. “But seeing the pillar (i-rei-to or memorial monument in the camp cemetery) against the backdrop of the mountain is just really powerful.”

When asked about how they felt about certain Congress members accusing CAIR of being a terrorist organization, Mughal said, “It’s a matter of gaining knowledge because when you look at the facts, CAIR does not associate itself with any terrorists. In fact, it has released a lot of statements opposing terrorism. The main focus of CAIR is not only to battle prejudice against Muslims but to also bridge the cultural gap.”

“It’s an ideological gap that people seem to have,” said Asalm. “So it’s a matter of showing that although we may seem different, we’re, in essence, all the same.” Fumie Ishii Shimada, who is active with the Florin JACL-CAIR program, said, “CAIR is not a terrorist group. CAIR is a very understanding organization. But in every religion or in any race, there will be a certain number of problem people but they are not involved in CAIR. Terrorists are not CAIR members.”

Roy Vogel, a Vietnam veteran, attended his third Manzanar Pilgrimage. After his stint in the military, Vogel said he studied in Taiwan and became an Asian studies major when he returned to the states.

“I sort of wondered why we were getting into these crazy wars in Asia and why we weren’t learning from history,” said Vogel. “I studied a lot of geography too. You just don’t get good history lessons in high school. All the textbooks are phony baloney.

“A lot of people in California still don’t know about the Japanese American experience, but there are a lot more people outside of California who have never even heard about it. The government and political people seem to like to keep minority issues out of the textbooks.”

Japan Connection

Hiroshi Inomata, the new consul general of Japan from the San Francisco area, is carrying on a tradition started by his predecessor, Consul General Yasumasa Nagamine, who in 2009 made a historic first by attending both the Manzanar and Tule Lake pilgrimages.

Inomata, who started in the San Francisco office last September, said he’d read books, seen photographs and viewed films on the camps, but nothing compared to actually being at the site.

“I thought I could imagine what kind of life they had led here,” said Inomota. “But putting my foot on this ground, I found that this was beyond my imagination. Those people who stayed here were forced to stay here without any freedom and were segregated from the free world, but the Issei and Nisei persevered, and the third and fourth generations became the bridge between the two countries of Japan and the United States.”

Inomata also gave his heartfelt appreciation to all the support Japan has been receiving in the aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake, the tsunami and the nuclear power plant collapse.

“With the help of all the countries, especially from the United States, we are very much grateful for that help,” said Inomata. “I want to take this opportunity to express my gratitude for giving us compassion and prayers and assistance. We really appreciate it, especially from California, although we’ve received help from all over the world. So this is important and it is our responsibility and duty to further strengthen and deepen our relationship between Japan and the United States.”

An NHK crew was also present to film footage of former camp garden sites. Speaking in Japanese, NHK Program Director Yo Ijuin said they are planning to produce a program on the Japanese gardens created at Manzanar.

“We learned that Manzanar had Japanese gardens, so today we came to talk to people who remember those gardens and the gardeners who worked on them,” said Ijuin. “Mr. Harry Ueno created a big garden at Block 22, so we filmed that area.”

Manzanar at Dusk

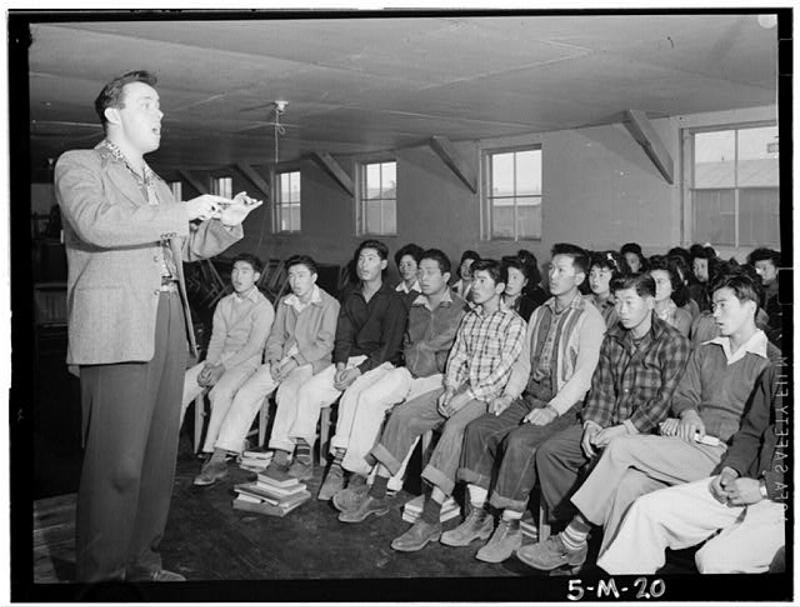

With so many former camp inmates passing away, the Manzanar at Dusk (MAD) program this year had college students present oral history interviews as an effort to share with the students about the wartime experience.

“We’re in a position now where we want to hear the stories, but how can we do that when so many are passing away?” said Gann Matsuda, MAD co-coordinator, who noted that MAD had originally been started by Jenni Kuida, Ayako Hagihara, and San Francisco City College students.

Since MAD had its roots with college students, Matsuda said this year they had college students take the lead by presenting three oral history interviews.

Jaymie Takeshita, a member of UCLA’s Nikkei Student Union (NSU), shared the experiences of her grand-aunt, Pat Takeshita.

Ashley Honma, another UCLA NSU member, wrote the narrative of Jun Yamamoto. It was presented by Michael Amutan, who even used the Rafu Shimpo as a prop.

The last narrative was written by Mika Kennedy from UC San Diego, who shared about Shigeko Sese Uno.

Great Aunt’s Story

Manzanar Park Ranger Richard Potashin said a common visitors’ question was what would motivate someone to work at Manzanar during the war. To shed some light on this question, he invited Susanne Norton La Faver, who gave a detailed presentation of her great aunt, Margaret Matthew d’Ille Gleason, who had served as Manzanar’s director of community welfare.

“Most of or stories and exhibits focus, rightly so, on the Japanese Americans incarcerated at Manzanar, but there were also other groups here,” said Potashin. “The War Relocation Authority was the civilian agency entrusted with the establishment and operation of these camps. Most of the staff was Caucasian, so here at Manzanar, we’ve been interviewing folks who worked as WRA staff members. Some of them came from great distances. Others were local people. Even Owens Valley Pauite Indians were hired as administrative staff here throughout the history of the camps, and their stories are very significant to us.”

La Faver is currently working on a book about her great aunt, who had worked in Japan for 10 years as the secretary of the National YWCA before being transferred to Siberia. She was 63 when she came out to Manzanar to become the chief of community welfare and head counselor. Her responsibilities included overseeing Manzanar’s Childrens’ Village, the orphanage.

Four decades earlier, d’Ille Gleason had met Ralph Merritt at UC Berkeley. The two crossed paths again at Manzanar, when Merritt was assigned as project director.

On Dec. 6 1942, a riot broke out at Manzanar, leaving two inmates dead and several injured. Merritt was under pressure to get tough but d’Ille Gleason suggested another option.

La Faver said each year at Christmas, her family recounts the story of how her great aunt helped restore peace at Manzanar. D’Ille Gleason reminded Merritt of his Christian faith and of the warehouse full of presents shipped to the camp by churches and friends. She suggested he distribute the presents and get the men into the mountains to cut Christmas trees.

Since she also oversaw Children’s Village, she proposed a party there on Christmas Eve. When the children started singing Christmas carols that eve, they heard other voices join in.

“Ralph got up and quietly walked out into the night,” said La Faver. “The clear moon and stars were shining over the Sierras. From out of the darkness, there came a great volume of Christmas carols that were being sung from the children outside the village.”

Merritt welcomed the sight. Then he, his wife Varinna and d’Ille Gleason walked through the camp, followed by hundreds of children and youths singing Christmas carols.

“Lights came on throughout the camp,” La Faver said, reading Merritt’s words. “Christmas greetings called out to us. Manzanar came alive. When we came to the spot where the riot had occurred and where men had been wounded and killed, we stood together, not in the spirit of anger, but in the Christmas spirit that recreated a new peace and good will at Manzanar.”

Closing Remarks

Bruce Embrey, son of Manzanar Committee founder Sue Kunitomi Embrey, recalled that when his parents first brought him to Manzanar as a child during the 1970s, there was nothing at the site except for the i-rei-to (literally, “soul-consoling tower”) in the cemetery and a deteriorating auditorium.

At that time, a few hundreds people came out. Most were former inmates or friends and families of former inmates. Today, participants have swelled to over 1,000 people with people coming from all nationalities and ages.

Embrey encouraged attendees to educate themselves about the history and not be afraid to share the experience with others. “We tell this painful story, not to shame anyone, not to make anyone feel uncomfortable,” he said. “Many people said ‘shikata ga nai.’ It can’t be helped. Don’t talk about this. You’re bringing shame to our community.

“Many people outside of the Japanese American community didn’t want it raised because it was an embarrassment. The truth can be painful but it is also useful. When you’re a small child and you touch the hot stove, you experience pain. You don’t touch that hot stove again….

“Our legacy, as a community that was systematically deprived of our civil rights, is to make sure America does not forget what happened. Our legacy is to ensure no other group, be they Muslim, Arab or any other group, be vilified and denied their civil and constitutional rights. That is our legacy."