Andrew Jackson at 250: President's legacy isn't pretty, but neither is history tennessean.com/story Historical reputations rise and fall; Jackson isn’t unique in this regard. But his case is peculiar in the extent of the fall and for what it says about historical memory. Oddly, Jackson’s reputation was the victim of his success. His sins were remembered because his achievements were so profound.

MARCH 15, 2017

MARCH 15, 2017

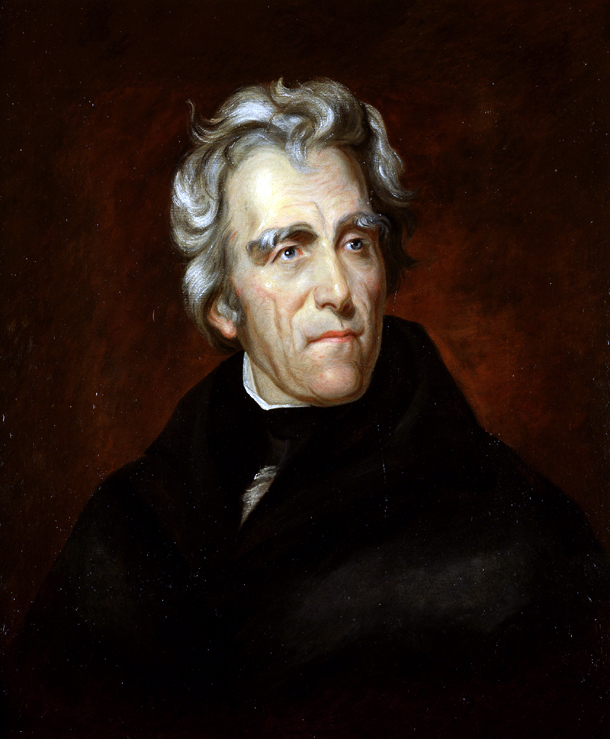

President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson called himself a Jeffersonian Democrat, while Thomas Jefferson called Jackson a dangerous man. Find out more about this "hero of the common man."

The first Irish-American president? The answer may surprise you. While John F. Kennedy was the first Irish-Catholic president, Andrew Jackson was the first chief executive with roots in the Emerald Isle. Check out that and nine other surprising facts about “Old Hickory.”

Jackson’s parents emigrated from Ireland.

Both of Jackson’s parents, Andrew and Elizabeth, were born in Ireland’s Country Antrim (in present-day Northern Ireland), and in 1765 they set sail with their two sons, Hugh and Robert, from the port town of Carrickfergus for America. The Jacksons settled with fellow Scotch-Irish Presbyterians in the Waxhaws region that straddled North and South Carolina.

The seventh president was born on March 15, 1767, but exactly where is disputed. The Waxhaws wilderness was so remote that the precise border between North and South Carolina had yet to be surveyed. In an 1824 letter, Jackson wrote that he had been told that he had been born in his uncle’s South Carolina home, but dueling historic markers in both states still claim to be the true locations of Jackson’s birthplace.

Jackson killed a man in a duel.

The fiery Jackson had a propensity to respond to aspersions cast on his honor with pistols. Historians estimate that “Old Hickory” may have participated in anywhere between 5 and 100 duels. When a man named Charles Dickinson called Jackson “a worthless scoundrel, a paltroon and a coward” in a local newspaper in 1806, the future president challenged his accuser to a duel. At the command, Dickinson fired and hit Jackson in the chest. The bullet missed Jackson’s heart by barely more than an inch. In spite of the serious wound, Jackson stood his ground, raised his pistol and fired a shot that struck his foe dead. Jackson would carry around the bullet in his chest as well as another from a subsequent duel for the rest of his life.

He won the popular vote for president three times.

Jackson captured nearly 56% of the popular vote in winning the presidency in 1828, and he nearly matched that figure four years later in his reelection. “Old Hickory” also won the most popular votes, although not a majority, in his first presidential run in 1824. Since no candidate won a majority of electoral votes, the 1824 election was thrown into the House of Representatives, which selected John Quincy Adams in what Jackson’s supporters claimed was a “corrupt bargain” with Speaker of the House Henry Clay, who was named secretary of state by Adams. In his annual messages to Congress, Jackson repeatedly lobbied for the abolition of the Electoral College.

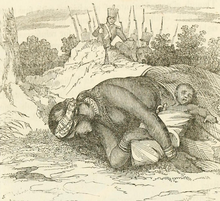

He was the target of the first attempted presidential assassination.

As Jackson was leaving the U.S. Capitol on January 30, 1835, following a memorial service for a congressman, a deranged house painter named Richard Lawrence fired a pistol at the president from just feet away. When Lawrence’s gun misfired, he pulled out a second weapon and squeezed the trigger. That pistol also misfired. An enraged Jackson charged Lawrence with his cane as the shooter was subdued. A subsequent investigation found the pistols to be in perfect working order. The odds of both guns misfiring were found to be 125,000 to 1.

Unbeknownst to Jackson, he married his wife before she had been legally divorced from her first husband.

After moving to Nashville, Tennessee, in the 1780s, Jackson fell in love with the unhappily married Rachel Donelson Robards. After she separated from her husband and believing that she was granted a legal divorce, Robards wed Jackson. In fact, however, the divorce had not yet been finalized, and her first husband accused her of adultery. Jackson legally remarried Robards in 1794, but the episode resurfaced in the nasty 1828 presidential campaign when Jackson’s political opponents spread the gossip about his wife’s alleged adultery. After Rachel Jackson died just weeks after her husband’s election, the grieving president-elect believed the anguish caused by the slander hastened her demise.

He was the only president to have been a former prisoner of war.

During the Revolutionary War, the 13-year-old Jackson joined the Continental Army as a courier. In April 1781, he was taken prisoner along with his brother Robert. When a British officer ordered Jackson to polish his boots, the future president refused. The infuriated Redcoat drew his sword and slashed Jackson’s left hand to the bone and gashed his head, which left a permanent scar. The British released the brothers after two weeks of ill treatment in captivity, and within days Robert died from an illness contracted during his confinement.

He adopted two Native American boys.

Although he led campaigns against the Creeks and Seminoles during his military career and signed the Indian Removal Act as president, Jackson also adopted a pair of Native American infants during the Creek War in 1813 and 1814. Orphaned himself at age 14, Jackson sent back to Rachel an infant orphan named Theodore, who died early in 1814, and a child named Lyncoya, who was found in his dead mother’s arms on a battlefield. “He is a savage that fortune has thrown in my hands,” Jackson wrote to his wife about the boy. Lyncoya died of tuberculosis in 1828, months before Jackson’s election.

He was a notorious gambler.

Jackson had a taste for wagering—on dice, on cards and even on cockfights. As a teenager, he gambled away all of his grandfather’s inheritance on a trip to Charleston, South Carolina. Jackson’s passion in life was racing and wagering on horses.

Chastened by a financial hit he once took from devalued paper notes, Jackson was opposed to the issuance of paper money by state and national banks. He only trusted gold and silver as currency and shut down the Second Bank of the United States in part because of its ability to manipulate paper money. It’s ironic that Jackson not only appears on the $20 bill, but his portrait in the past has also appeared on $5, $10, $50 and $10,000 denominations in addition to the Confederate $1,000 bill.

REFERENCE: history.com/news