By Tim Arango from The New York Times

originally published Dec. 5, 2018

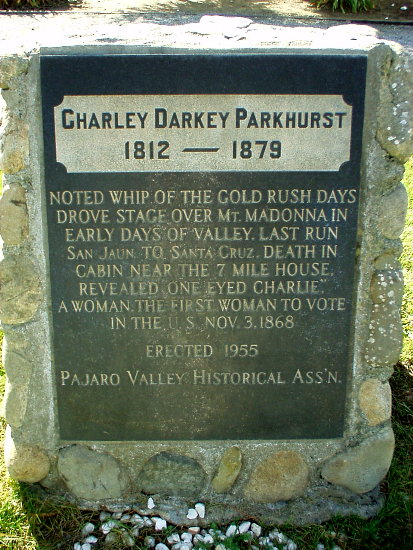

Overlooked No More: Charley Parkhurst, Gold Rush Legend With a Hidden Identity

A swashbuckling, one-eyed stagecoach driver lived her life disguised as a man. After her death, the revelation that she was a woman provoked widespread astonishment.

Charley Parkhurst was a legendary driver of six-horse stagecoaches during California’s Gold Rush — the “best whip in California,” by one account.

The job was treacherous and not for the faint of heart — pulling cargos of gold over tight mountain passes and open desert, at constant peril from rattlesnakes and desperadoes — but Parkhurst had the makeup for it: “short and stocky,” a whiskey drinker, cigar smoker and tobacco chewer who wore a black eyepatch after being kicked in the left eye by a horse.

And there was one other attribute, this one carefully hidden from the outside world. When Parkhurst died in 1879 at age 67, near Watsonville, Calif., of cancer of the tongue, a doctor discovered that the famous stagecoach driver was biologically a woman. Charley, it turned out, had been short for Charlotte.

“The discoveries of the successful concealment for protracted periods of the female sex under the disguise of the masculine are not infrequent, but the case of Charley Parkhurst may fairly claim to rank as by all odds the most astonishing of them all,” The San Francisco Call wrote not long after her death, in an article that was reprinted in The New York Times under the headline “Thirty Years in Disguise.”

Charlotte Darkey Parkhurst was born in 1812 in New Hampshire. Abandoned by her parents, she was consigned to an orphanage, from which historians believe she ran away wearing boys’ clothes. She wound up in Worcester, Mass., where she got a job cleaning horse stables. She also found a mentor, Ebenezer Balch, who taught her how to handle horses.

“The story goes that while in the poor house he discovered that boys have a great advantage over girls in the battle of life, and he desired to become a boy,” The Providence Journal in Rhode Island wrote in an article after her death, as reporters on both coasts tried to piece together her life.

After working as a stagecoach driver on the East Coast for several years, Parkhurst journeyed west, like so many Americans seeking fortune and reinvention in California. She traveled by ship to Panama, traversed a short overland route, and then boarded another ship to San Francisco, where she arrived in 1850 or 1851.

In California, she quickly became known for her ability to move passengers and gold safely over important routes between gold-mining outposts and major towns like San Francisco or Sacramento. “Only a rare breed of men (and women),” wrote the historian Ed Sams in his 2014 book “The Real Mountain Charley,” “could be depended upon to ignore the gold fever of the 1850s and hold down a steady job of grueling travel over narrow one-way dirt roads that swerved around mountain curves, plummeting into deep canyons and often forded swollen, icy streams.”

Parkhurst wore “long-fingered, beaded gloves,” Sams wrote, to hide her feminine hands. She was considered one of the safest stagecoach drivers — not a daredevil, like so many of her contemporaries — and had a special rapport with the horses. She drove for Wells Fargo, at least once moving a large cargo of gold across the country.

A 1969 article about Parkhurst in the Travel section of The New York Times evoked some of the perils she faced: “Indians and grizzly bears also were a major menace. The state lines of California in the post-Gold Rush period were certainly no place for a lady, and nobody ever accused Charley of being one.”

“The only feminine trait her acquaintances could recall,” the article added, “was her fondness for children.”

Once she was kicked in the eye by a horse, which was perhaps startled by a rattlesnake; that earned her the nickname “One-Eyed Charley,” for the black patch she wore over her left eye.

Parkhurst’s story has long been shrouded in myth and thinly sourced anecdotes. (A well-worn tale has her killing a famous bandit known as Surgarfoot after he held up her stagecoach on the route between Mariposa and Stockton.)

In “Charley’s Choice,” a 2008 work of historical fiction, the writer Fern J. Hill imagines that as a child, Parkhurst told a friend of her dreams of driving a stagecoach. When the friend replied, “You can’t, you’re a girl,” young Charlotte decided then and there to live as a man.

And in another novel, “The Whip,” by Karen Kondazian (2012), Parkhurst is cast as a straight woman who wanted her freedom.

“I would have done that,” Ms. Kondazian said in a telephone interview. “I would have probably put on men’s clothes, to be free like a man.”

She added: “You can kind of use her in any way you want, because we don’t have the total facts about her.”

Some historians say that had Parkhurst lived today, she might well have identified as gay or transgender. “Being gay at that time was seen as negative,” said Mark Jarrett, a textbook publisher who included Parkhurst in a new book intended to comply with a California law requiring social studies curriculums to recognize the historical role of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.

“It was illegal, it was a crime,” he said, “so people didn’t go around professing what their real identities were. They were hidden identities.”

In the late 1860s, with the growing popularity of railroads, stagecoach driving became a dying profession. Parkhurst retired and opened a saloon for a time, and also worked as a lumberjack in Northern California. After she died, The Santa Cruz Sentinel wrote, “Her accumulations were regular and her wealth considerable at the time of her death, which took place in a lonely cabin, with no one near and her secret her own.”

Parkhurst could claim one other distinction: An 1867 registry in Santa Cruz County lists a Charles Darkey Parkhurst from New Hampshire as having registered to vote — more than 50 years before the 19th Amendment gave women the franchise. While there is no evidence she voted in the 1868 presidential election, her gravestone in Watsonville is etched with these words: “The First Woman to Vote in the U.S.” (The claim is generally doubted by historians.)

Even in the 19th century, however, there was admiration for Parkhurst’s feat of disguise.

“The only people who have occasion to be disturbed by the career of Charley Parkhurst are the gentlemen who have so much to say about ‘woman’s sphere’ and ‘the weaker vessel,’ ” The Providence Journal wrote. “It is beyond question that one of the soberest, pleasantest, most expert drivers in this State, and one of the most celebrated of the world-famed California drivers was a woman. And is it not true that a woman had done what woman can do?”